Pairing Your Tea and Teaware, A Regional Approach

For some of us, selecting the teaware we plan to use on any given day is an emotional or aesthetic decision. We might feel good about a gaiwan one day and a teapot the next, or we might simply find that the Yixing teapot looks more attractive next to the stoneware teacups.

For others, teaware selection is a functional choice. When tea is infused at a lower temperature, for instance, these types will display a strong preference for thinner-walled gaiwans and teacups, and as the temperature requirement increases, they’ll try to make sure to choose teaware that is more insulated. After all, nobody wants to risk burning their fingers or ruining their favorite cup of tea.

But did you know there’s another way to pair your teaware with your tea (and it works quite well)? The short answer is this: think regionally. Who better understands what kind of teaware gets the most out of their tea than the locals who have been drinking this tea for centuries? There is a close relationship between indigenous artists, their ceramic tradition, and the native cultivars—they designed and sculpted their wares for their teas.

Artists in Jingdezhen, for instance, were most familiar with the more delicate green teas from Anhui and Fuliang. It is therefore no surprise to discover the explosion in popularity of paper thin, translucent porcelain. It added a heavenly quality to the already soft, delicate teas.

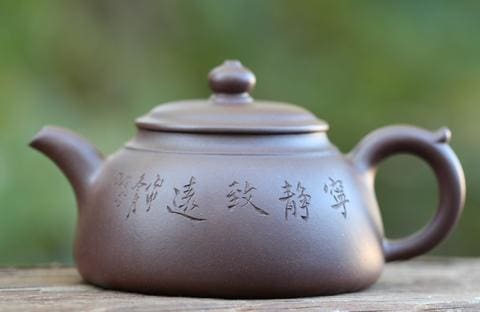

Meanwhile, far away to the southwest China of Yunnan, while tea masters were crafting black teas and pu erhs. Jian Shui tea wares afforded an appropriate level of insulation and heat retention, meeting the optimal brewing requirements for these darker teas. As a bonus, the porous clays of these wares absorbs the flavors of these teas, helping ensure they only taste more and more flavorful over time.

However, when you travel due south from Jingdezhen instead, you’ll find Fujian. Home to inimitable white teas and Wuyi rock oolongs, the tradition here has been to use celadon, Jian Zhan, and even Qing Ci teawares. To accommodate the very different types of local teas, the pottery had to become more flexible and diverse. When you apply a celadon glaze to stoneware, for instance, it is heavy enough to handle roasted oolong, but it is also smooth and light enough to work with green teas.

Finally, in Huangzhou, where the highly coveted dragonwell green tea is produced, the crackled, sky-blue glaze of ruware was the preferred choice during the Song Dynasty. Often unadorned and emphasizing form, these low-fired wares take on a life of their own with frequent use as the crackles deepen in color and create spectacular, three-dimensional patterns.

While this approach works most of the time, there are some limitations to it. Tea production methods and even tea cultivars are always evolving, and so some regions will experiment by crafting new, exotic teas that have not been part of that region’s tradition. If you plan on enjoying one of these teas, then you’ll need to be a little more judicious with your teaware choice.

But for the most part, thinking regionally takes both the aesthetic and functional considerations out of the equation for us while leaving us with quite reliable choices. After all, it was a quite lengthy, trial-and-error history that dictated these choices as artists slowly learned what worked and what didn’t. By thinking along these lines, we too participate in that history, keeping it alive and well.